Japanese Sake: The Complete Guide to Japan’s Traditional Rice Wine

While sake has been Japan’s national beverage for over a millennium, its popularity across Asia is at an all-time high. Rooted in Japan's traditional brewing methods and centuries-old origins. It symbolizes Japan's cultural heritage and craftsmanship. Understanding this complex brewed alcoholic beverage opens doors to a rich world of flavor, culture, and craftsmanship.

Often mistaken as simply “rice wine,” sake represents one of the world’s most sophisticated fermentation processes, blending ancient Japanese culture with modern precision. In recent years, sake has joined wine and beer in the global beverage scene, offering refreshing taste profiles that complement everything from traditional Japanese cuisine to contemporary Asian fusion dishes.

What is Sake?

Sake, known as nihonshu in Japan, is a traditional alcoholic beverage made by fermenting polished rice grains. Unlike wine, which ferments grape sugars directly, or distilled spirits requiring distillation, sake undergoes a unique brewing process called multiple parallel fermentation. This complex method converts rice starch into fermentable sugars using koji mold, while yeast simultaneously ferments those sugars into alcohol. The sake production process—including rice polishing, koji cultivation, and fermentation techniques—determines the quality, flavor, and classification of sake.

Is it an alcoholic drink?

Most sake contains 15-20% alcohol, placing it between wine (12-15%) and spirits (40%+). This makes sake stronger than beer but more approachable than distilled alcohol, versatile as both a sipping drink and food pairing companion. The resulting sake ranges from clear to slightly golden, with flavors from crisp and dry to rich and sweet.

The term “sake” technically means any alcoholic drink in Japanese, but internationally it specifically refers to this rice-based beverage. True sake must be produced using specific ingredients and methods, setting it apart from other rice wines in Asia. The brewing process shares similarities with beer, as both convert starches to sugars before fermentation, yet sake’s unique koji cultivation and rice polishing create distinct flavor profiles.

The Art of Sake Brewing

Sake brewing is one of the most intricate alcoholic beverage production methods worldwide. Central to it is cultivating koji mold (Aspergillus oryzae) on steamed rice, producing enzymes that break down rice starch into fermentable sugars. Flavors are also extracted from rice solids, enhancing aroma and quality. This parallel fermentation, where starch conversion and alcohol fermentation occur simultaneously, sets sake apart from other alcoholic drinks.

Traditional brewing starts with rice polishing, where machinery removes outer rice layers to access the starchy core. Polishing can remove 10% to 65% of the grain. Higher-grade sake requiring more polishing. This affects flavor, as more polished rice yields cleaner, refined tastes.

The brewing process includes inoculating steamed rice with koji spores in temperature-controlled environments, then preparing the yeast starter (shubo or moto) by mixing koji rice, steamed rice, water, and selected sake yeast. This starter ferments about two weeks, establishing the environment for main fermentation.

Temperature control is crucial. Unlike beer brewing at warm temperatures, sake ferments at low temperatures over longer periods (18-32 days), preserving delicate flavors and allowing complex profiles to develop.

Premium Sake Rice Varieties

Premium sake uses special rice called sakamai, differing from table rice in structure and composition. The prized Yamada Nishiki, called the “king of sake rice,” has large grains, low protein, and concentrated starch, allowing extensive polishing while maintaining integrity.

Rice varieties affect sake characteristics. Modern production matches rice varieties with brewing techniques for desired profiles.

- Gohyakumangoku rice, common in northern regions, produces clean, crisp sake with subtle flavors.

- Omachi, one of Japan’s oldest varieties, yields rich, complex flavors with pronounced umami.

Rice polishing ratio (seimai buai) indicates the percentage of grain remaining after polishing. Higher-grade sake requires lower ratios—junmai ginjo uses rice polished to 60% or less, daiginjo to 50% or less. More polishing means more rice is needed to produce the same amount of sake, affecting cost and quality perception. The polishing process can take days or weeks, with machinery removing layers carefully to avoid heat damage.

Types and Classifications of Sake

Sake classification is based on rice polishing, added alcohol, and production methods. The highest tier, special-designation sake (tokutei meishoshu), includes six main categories that guide consumers on quality and flavor.

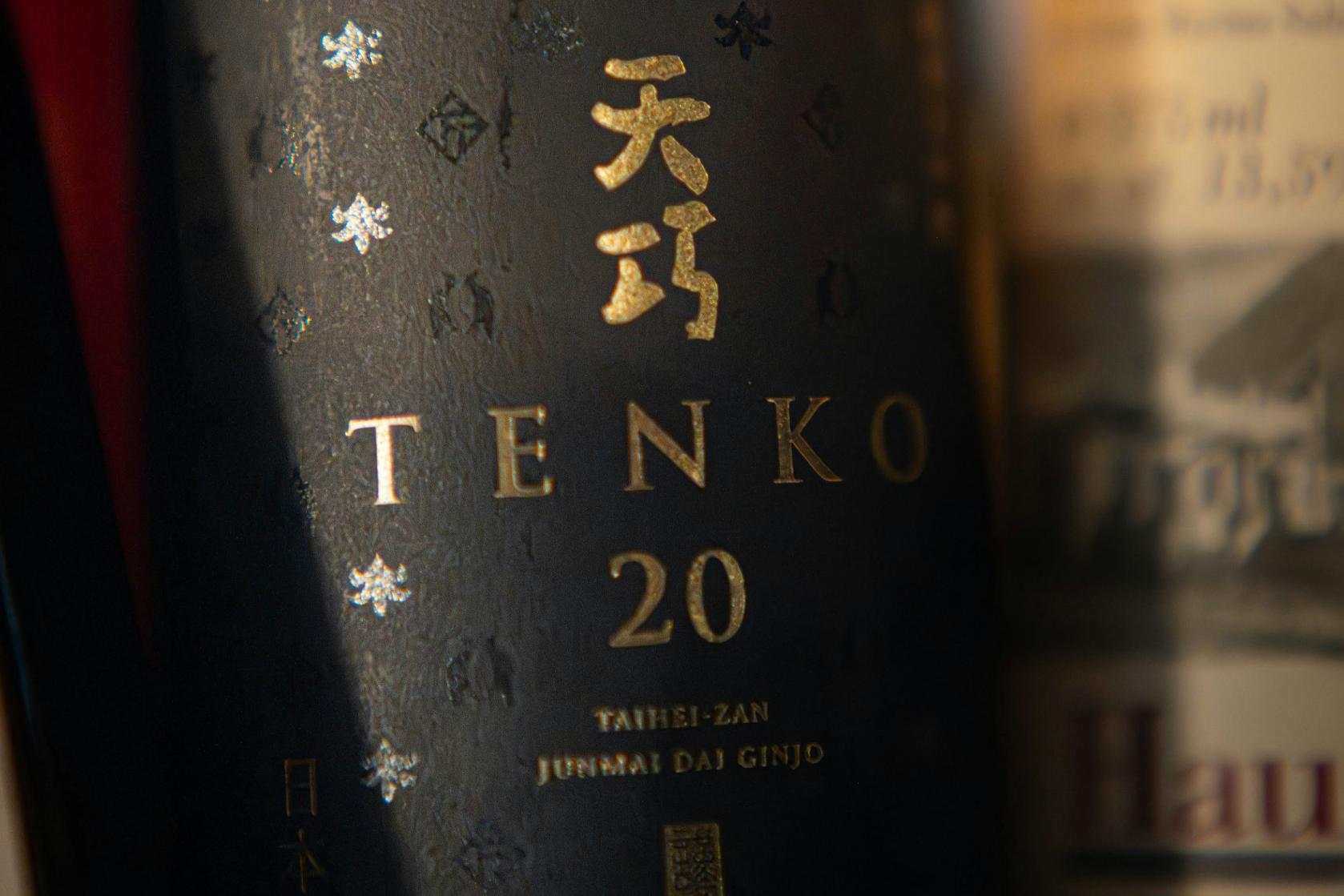

Junmai is pure rice sake with no added alcohol, using only rice, water, yeast, and koji. It features full-bodied flavors with rich umami. Junmai ginjo (rice polished to 60% or less) and junmai daiginjo (50% or less) offer more delicate, aromatic expressions.

Honjozo includes a small amount of brewer’s alcohol added during fermentation, mellowing flavor, enhancing aroma, and lightening profiles. Ginjo and daiginjo require specific polishing (60% and 50%) and often showcase elegant, fruity aromas popular in specialty sake bars worldwide.

| Sake Type | Rice Polishing Ratio | Added Alcohol | Typical Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Junmai | 70% or less | None | Full-bodied, rich umami |

| Honjozo | 70% or less | Small amount | Clean, light, approachable |

| Junmai Ginjo | 60% or less | None | Fruity, complex, balanced |

| Ginjo | 60% or less | Small amount | Elegant, aromatic, refined |

| Junmai Daiginjo | 50% or less | None | Delicate, sophisticated, premium |

| Daiginjo | 50% or less | Small amount | Ultra-refined, highest grade |

Premium vs. Regular Sake

Premium sake, the special-designation categories, meets strict polishing and production standards. Regular sake (futsuu-shu), the majority of production, has fewer restrictions and often more added alcohol and ingredients.

High-grade sake commands higher prices due to intensive polishing, extended fermentation, and smaller batches. Premium bottles range from $30 to $300+, while regular sake costs $10-25, suitable for everyday drinking. The best sake comes from renowned breweries with centuries of experience, though excellent examples exist at all price points.

Other sake types include unpasteurized sake, cloudy sake, and those made with different methods, highlighting sake’s diversity.

Understanding classifications helps consumers choose based on occasion and budget. Premium sake shines in special settings and food pairings, while quality regular sake suits casual drinking sake.

Proper Serving Methods and Temperatures

Temperature greatly affects sake’s flavor, making serving techniques vital. Unlike wine’s consistent serving temps, sake types show best at varying temperatures. Cold sake (5-10°C) preserves aromatics in premium ginjo and daiginjo, while room temperature (20°C) brings out complex flavors in robust junmai.

Traditionally, sake is heated in ceramic tokkuri vessels and poured into small cups (ochoko) or shallow saucers (sakazuki). Sake is served in units called 'go,' with 'ichi go' meaning one serving and 'ni go' two servings, common in bars and restaurants. Hot sake, or atsukan (50-55°C), intensifies umami and offers a warming experience for cold weather. However, heating premium sake can mask subtle flavors, so served chilled is preferred for these.

Modern service often uses wine glasses for premium sake, as the broader bowl concentrates aromatics and allows better temperature control. Wooden masu boxes, once used for measuring rice, add subtle cedar notes to the drinking experience. Serving vessel choice enhances sake appreciation, from cultural authenticity to flavor delivery.

Sake pouring etiquette stresses mutual service—never pouring your own cup but keeping others’ filled. This custom reinforces sake’s role in building relationships and community, whether in business or family gatherings.

Sake and Food Pairing

Sake’s natural umami makes it exceptionally food-friendly, enhancing rather than competing with flavors. Its clean finish and neutral pH complement delicate dishes, while subtle sweetness balances spicy or salty foods. Sake is often compared to white wine for its light, dry profile and similar serving temperatures, making it versatile. Sparkling sake, reminiscent of sparkling wine, offers a bubbly, enjoyable experience popular with beginners. Traditional Japanese cuisine pairs naturally with sake, both evolving over centuries.

Classic pairings include sake with sushi and sashimi, where sake’s clean profile doesn’t overpower fresh fish and its acidity cuts through fatty textures. Tempura’s light, crispy texture matches well with crisp, dry sake that refreshes the palate. Yakitori and grilled dishes benefit from sake’s ability to complement sweet glazes and smoky flavors.

The sake meter value (SMV) guides pairing:

- Dry sake (positive SMV) suits salty or rich foods.

- Sweet sake (negative SMV) pairs with spicy dishes or desserts.

Understanding these helps match sake styles with foods for optimal harmony.

Sake with Asian Cuisines Beyond Japan

Sake’s versatility extends beyond Japanese cuisine, complementing diverse Asian cooking. Chinese dishes like dim sum pair with delicate ginjo sake, while robust junmai suits rich Peking duck or spicy Sichuan food. Sake’s umami complements soy-based sauces and fermented ingredients common in Chinese cooking.

Korean cuisine offers exciting pairings, especially with kimchi’s tanginess and Korean BBQ’s bold flavors. Sake’s clean finish cuts through rich meats, and its sweetness balances kimchi’s spice. Korean restaurants often feature sake alongside soju, highlighting complementary qualities.

Thai cuisine’s complex flavors—sweet, sour, salty, spicy—find harmony with various sake styles. Light, crisp sake suits seafood and fresh herbs, while fuller-bodied types hold up to rich coconut curries. Vietnamese cuisine, emphasizing fresh ingredients and delicate broths, pairs well with clean, refreshing sake styles.

Sake’s growing presence in pan-Asian fusion restaurants reflects its adaptability. Chefs increasingly see sake as a wine alternative offering unique benefits in Asian culinary contexts.

Cultural Significance and History

Sake’s origins date back over 1,500 years, with evidence of rice fermentation during the Yayoi period (300 BCE–300 CE). Early methods involved chewing rice to start fermentation via saliva enzymes—a practice called kuchikami-sake. Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines refined brewing techniques, with monks perfecting fermentation and setting quality standards.

In the Heian period (794–1185), sake became integral to imperial ceremonies and religious rituals. Its spiritual role continues in Shinto practices, used as offerings and in purification, weddings, and festivals. Participants often became drunk during these celebrations, showing sake’s role beyond sacred offerings to communal enjoyment. This sacred aspect elevates sake from mere drink to cultural and spiritual expression.

The Edo period (1603–1868) was sake’s golden age, with standardized production and regional styles. Taxation encouraged quality, and transport spread regional varieties across Japan. Many breweries from this era still operate, blending tradition with modern innovation.

Today, sake remains central to Japanese culture, adapting to modern social settings. Business relationships often develop over sake sharing, with elaborate etiquette for serving and receiving. Family celebrations, seasonal events, and community festivals keep sake traditions alive across generations.

Regional Sake Varieties

Japan’s geography and climate create distinct regional sake styles. The Nada region in Hyogo Prefecture, sake’s birthplace, produces bold, robust styles using mineral-rich hard water, resulting in pronounced flavors and strong structure with higher acidity, pairing well with rich foods.

Niigata Prefecture is known for crisp, clean sake emphasizing purity and subtle elegance. Its soft water and cold climate foster delicate flavors and smooth finishes. Niigata sake is often dry with minimal sweetness, ideal for seafood.

The Fushimi district in Kyoto produces gentle, refined sake from exceptionally soft water, enabling delicate fermentation that preserves subtle flavors and smooth textures. Fushimi sake balances sweetness and acidity, approachable for newcomers and complex for connoisseurs.

The jizake movement celebrates small, local producers emphasizing traditional methods and unique regional expressions. These artisanal breweries experiment with heritage rice, wild yeast, and aging to create distinctive products reflecting their terroir.

Famous Sake Breweries

Sudo Honke, founded in 1141, is Japan’s oldest continuously operating sake brewery, preserving ancient methods with modern quality controls. Their products bridge historical authenticity and contemporary standards. Visiting such historic breweries offers insight into sake’s evolution and refinement.

Modern premium producers like Dassai have revolutionized sake appreciation with innovative marketing and consistent quality. These breweries focus on single rice varieties and specific methods, creating signature styles with devoted followings. Many share detailed production info and encourage direct consumer connections.

Brewery tourism is popular, with many offering tours, tastings, and education. Visitors can experience brewing firsthand and sample fresh, unpasteurized sake rarely found commercially.

Sake’s Growing Popularity Across Asia

Sake consumption in Asia has surged, with exports reaching record levels. China leads growth, with imports up over 300% since 2015, driven by rising incomes and appreciation for premium Japanese products. Young Chinese consumers see sake as sophisticated and trendy.

South Korea’s sake market has exploded alongside the Korean Wave, with strong preferences for premium varieties. Seoul hosts many specialty sake bars featuring renowned Japanese producers. Korean restaurants increasingly pair sake with traditional dishes, creating fusion experiences.

Southeast Asian markets like Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam show remarkable sake adoption. Thai consumers appreciate sake’s fit with complex local flavors; Vietnamese markets favor lighter styles complementing fresh, herb-heavy cuisine.

Sake in Modern Asian Dining

Asian restaurants increasingly feature sake, often with certified professionals guiding selections and pairings. Many offer sake flights to compare styles and develop preferences. Sake tasting events provide authentic flavor experiences. The trend toward premium sake reflects growing consumer sophistication and willingness to invest in quality.

Sake cocktails are popular in Asian nightlife, with bartenders creating innovative drinks highlighting sake’s versatility. These drinks introduce sake to new audiences beyond traditional service. Popular cocktails often use Asian ingredients like yuzu, shiso, or lychee, creating culturally relevant flavors.

High-end restaurants maintain extensive sake cellars with rare and aged varieties, reflecting sake’s elevation from ethnic specialty to a sophisticated beverage category.

How to Select Quality Sake

Selecting quality sake involves understanding labels and reputable producers. Identify categories—junmai, ginjo, daiginjo—to gauge quality. Rice polishing percentages indicate refinement; lower numbers usually mean higher price and delicate flavors.

Brewery reputation matters; historic producers often ensure consistent quality, and award-winning breweries are safe choices. Many labels include production details like rice variety, water source, and fermentation method.

Storage affects quality. Most sake doesn’t improve with age and should be consumed within 1-2 years. Namazake (unpasteurized) needs refrigeration and quick consumption but offers vibrant, fresh flavors. Check production dates and choose fresh bottles.

Beginner-Friendly Recommendations

New drinkers should start with approachable styles showing sake’s range without overwhelming. Junmai ginjo is ideal, with fruit aromatics and balanced sweetness appealing to wine drinkers.

Avoid very dry or earthy varieties initially, as they may discourage exploration. Also, very expensive bottles may set unrealistic expectations. Focus on mid-range reputable producers to develop your palate.

Try various styles—junmai, ginjo, nigorizake (cloudy sake)—to find preferences. Specialty retailers offer tasting sets or small bottles for sampling. Online shops provide tasting notes and pairing suggestions.

Sake Storage and Enjoyment Tips

- Proper storage preserves quality and prevents flavor loss. Store sake upright in cool, dark places like refrigerators at 40-50°F. Avoid light exposure, which causes off-flavors and color changes, especially in clear bottles.

- Opened sake stays good for days to weeks depending on type and storage. Unpasteurized varieties need immediate refrigeration and quick use; pasteurized sake lasts longer. Vacuum-sealing helps reduce oxidation.

- Serve sake in small portions (1.5-2 ounces) for slow appreciation and social drinking. Clean, neutral glasses prevent flavor interference. Experiment with serving temperatures to find what enhances your enjoyment.

- Build a collection balancing variety and storage. Include major categories and regions for tasting diversity. Sparkling sake adds bubbly, refreshing options for newcomers. Seasonal and limited releases offer special occasions, while everyday sake serves regular enjoyment.

Whether you’re starting your journey or expanding appreciation, understanding sake’s heritage and production enriches every sip. From specialty bars to home pairings, sake offers endless discovery and enjoyment. Visit a local Japanese restaurant or retailer to experience why this ancient beverage captivates enthusiasts across Asia and beyond. For more insights, recipes, and guides on sake and Asian cuisine, explore Eat Drink Asia, your go-to resource for authentic Asian food and drink experiences.

When the Izakaya Becomes the Plan: Izakaya Singapore Beyond Dinner

Dio Asahi | January 27, 2026

As you step behind the humble noren curtain, you’re enveloped by the glow of lanterns, the sizzle of charcoal grilled skewers, and a resounding welcome from staff. This is izakaya, Japan’s answer to the gastropub and a beloved staple in Singapore’s vibrant dining landscape. But there’s far more to the izakaya Singapore experience than just…

Yuja Tea: Korea’s Traditional Citron Tea

Dio Asahi | January 27, 2026

The golden, aromatic steam rising from a cup of yuja tea carries centuries of Korean tradition and wellness wisdom. This caffeine-free citrus beverage has warmed Korean hearts through countless winters, offering both comfort and powerful health benefits in every sip. Made from the Korean citron known as yuja fruit, this simple Korean tea represents one…

The Global Phenomenon of Korean Instant Noodle: A Cultural and Culinary Journey

Eda Wong | January 24, 2026

In the high-octane streets of South Korea, where the “pali-pali” (hurry-hurry) culture defines the pace of life, one dish stands as the ultimate equalizer of speed and satisfaction: Korean ramyeon. While the world often uses the terms ramen and ramyeon interchangeably, the Korean version is a distinct entity. It is not merely a quick snack…

Traditional Ramyeon: The Soulful Heart of Korean Noodle Culture

Eat Drink Asia Team | January 20, 2026

In the bustling culinary landscape of South Korea, few comfort foods can match the satisfaction of a steaming bowl of ramyeon. While outside of Korea, “ramyeon” often brings to mind Korean instant noodles or instant ramen, true ramyeon Korean style refers to the artful, freshly prepared noodle soup enjoyed in homes and at local restaurants…

The Heart of the Korean Noodles: History and Texture

Eda Wong | January 17, 2026

In Korea, a bowl of noodles is far more than a simple dish; it is a cultural anchor that has weathered centuries of change. For generations, the length of the strand has symbolized a long and prosperous life, making Korean noodles a staple at birthdays, weddings, and the milestone 60th birthday celebration known as hwangap….

Preserving the ‘Big Bowl’ Tradition with Pen Cai Delivery in the Age of Doorstep Dining

Eat Drink Asia Team | January 15, 2026

Modern Festive Menu: Bringing the Big Bowl Home There is a special, undeniable magic to the Chinese New Year reunion dinner. For many families, Chinese New Year 2026 is another chance to gather loved ones at the table and celebrate with a glorious pen cai—sometimes called the “big bowl feast”—overflowing with premium ingredients and festive…

Sencha: Traditions, Flavors, and the Essence of Japanese Tea

Eat Drink Asia Team | January 15, 2026

When people around the world think of Japanese tea, images of tranquil tea ceremonies in small rooms or frothy bowls of matcha often come to mind. Yet, the reality of tea drinking in Japan is much broader, woven deeply into the culture and daily habits. For the vast majority, sencha is the beloved tea that…

The Best Restaurants Tokyo Are Rarely the Ones You Plan For

Eda Wong | January 12, 2026

Tokyo, Japan’s capital, does not reward urgency. It rewards return. On my first visit, I chased what everyone told me were the best restaurants Tokyo had to offer. I spent weeks highlighting maps, bookmarking digital “must-eat” lists, and refreshing reservation pages until my eyes blurred. I thought that by conquering the top-tier establishments, I would…

Japan and Food: Culinary Harmony – The Deep Connection Between Japanese Food and Culture

Eat Drink Asia Team | January 11, 2026

When it comes to Japan and food, the two are intertwined in ways that captivate taste buds and awaken the senses. Japanese cuisine stands as one of the world’s most revered traditions—more than nourishing meals, it is an art reflecting centuries of philosophy and a window into Japanese culture itself. Every bowl of miso soup,…

The Verdant Cup: A Celebration of Green Tea in Japan

Eda Wong | January 10, 2026

In Japan, green tea is much more than a beverage. It marks a moment of pause, hospitality, and tradition. The story of green tea in Japan weaves through centuries of culture, artistry, and daily life—bridging ancient rituals like the Japanese tea ceremony to everyday meals enjoyed at home. The origins and beginning of Japanese tea…