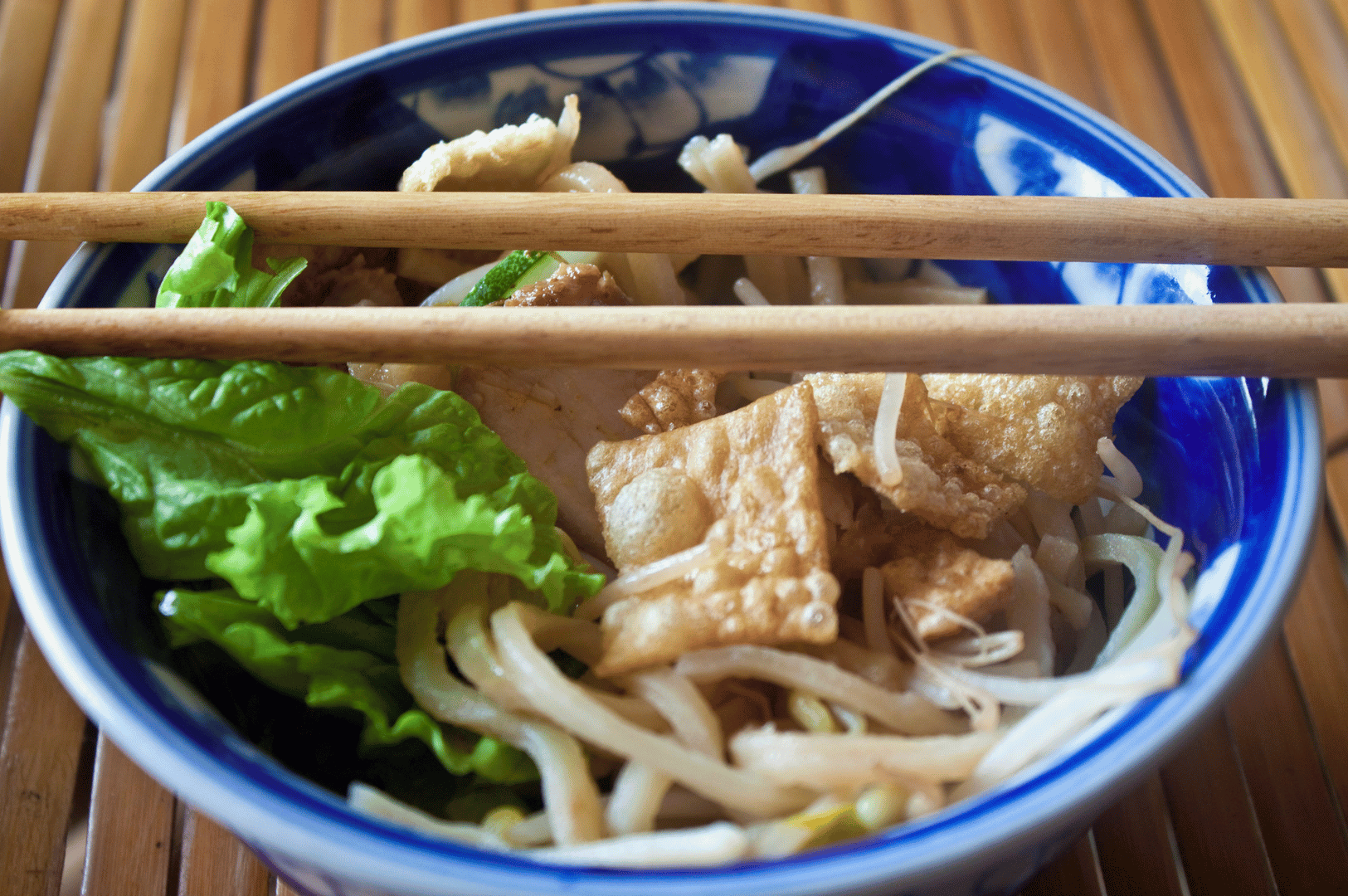

Imagine sitting on a low stool in a bustling alleyway of Hoi An's ancient town. The warm, fragrant air is thick with the scent of sizzling marinated pork, fresh herbs, and the unmistakable aroma of fish sauce and fried rice crackers. In front of you, a bowl of Cao Lau noodles gleams, their golden brown ribbons nestled beneath generous pork slices, crisp pork crackling, crunchy bean sprouts, and sprigs of fresh green vegetables from the famed Tra Que Vegetable Village. This noodle dish, renowned for its unique lye water noodles and deep ties to Vietnamese cuisine, is rarely found outside the same region in Central Vietnam, and every bite offers a tangy, smoky, and savory taste that's as mysterious and captivating as Hoi An itself.

Cao Lau is more than just a meal; it's a culinary icon rooted deeply in Vietnamese cuisine and food traditions of the ancient town. This authentic Cao Lau can be experienced only in Hoi An, thanks to its use of hyper-local ingredients like lye solution from the Ba Le well and ash from Cham Island. Whispers of Japanese cuisine echo in the unique noodles, while hints of Chinese flavors linger in the pork marinade and char siu pork—making this a noodle dish unique to Vietnam, but unmistakably shaped by centuries of culinary exchange. In this article, we’ll explore Cao Lau history, dive into its ingredients, the special role of fresh herbs and vegetable village greens, and the age-old traditions of preparing and serving this beloved Hoi An specialty.

The Mysterious Origins of Cao Lầu in Hoi An

Understanding Cao Lau requires stepping back into the 16th and 17th centuries, when Hoi An was Southeast Asia’s most vibrant trading port. Merchants from Japan, China, Portugal, the Netherlands, and elsewhere arrived, each bringing food traditions and flavors that transformed the city’s table. The Japanese, in particular, left a visible and lasting impact: the noodle dish's thick, chewy texture suggests a Japanese influence, reminiscent of udon and central aspects of Japanese cuisine. The iconic Japanese Covered Bridge still stands today, marking the ancient town's layered past.

Cao lau noodles are thought to have originated from this melting pot, with many linking their signature texture to Japanese influence on Vietnamese food. Local legends describe Japanese traders using Vietnamese rice, Ba Le well water, and lye solution to craft noodles reminiscent of their homeland. Others instead point to the flavors of char siu pork and Chinese marinade—soy sauce, garlic, sugar, salt, and pepper—as evidence of a Chinese touch. Some even connect the crispy noodle croutons to Chinese cuisine, or note how the minimal broth, fresh green vegetables, and fresh greens are distinctly Vietnamese staples found in celebrated noodle dishes across the region.

Despite these theories, the true Cao Lau history remains shrouded in mystery. Was it a gift from Japanese cuisine, an evolution of Chinese noodle dishes, or a product of culinary fusion unique to Central Vietnam? At first glance, no dish exemplifies Hoi An’s adaptability and creativity more; the truth, as locals say, is probably as layered as the meal itself—layered with bean sprouts, lettuce, unique noodles, fried rice crackers, and savory pork.

The Unique Ingredients of Cao Lầu Noodles and Grilled Pork

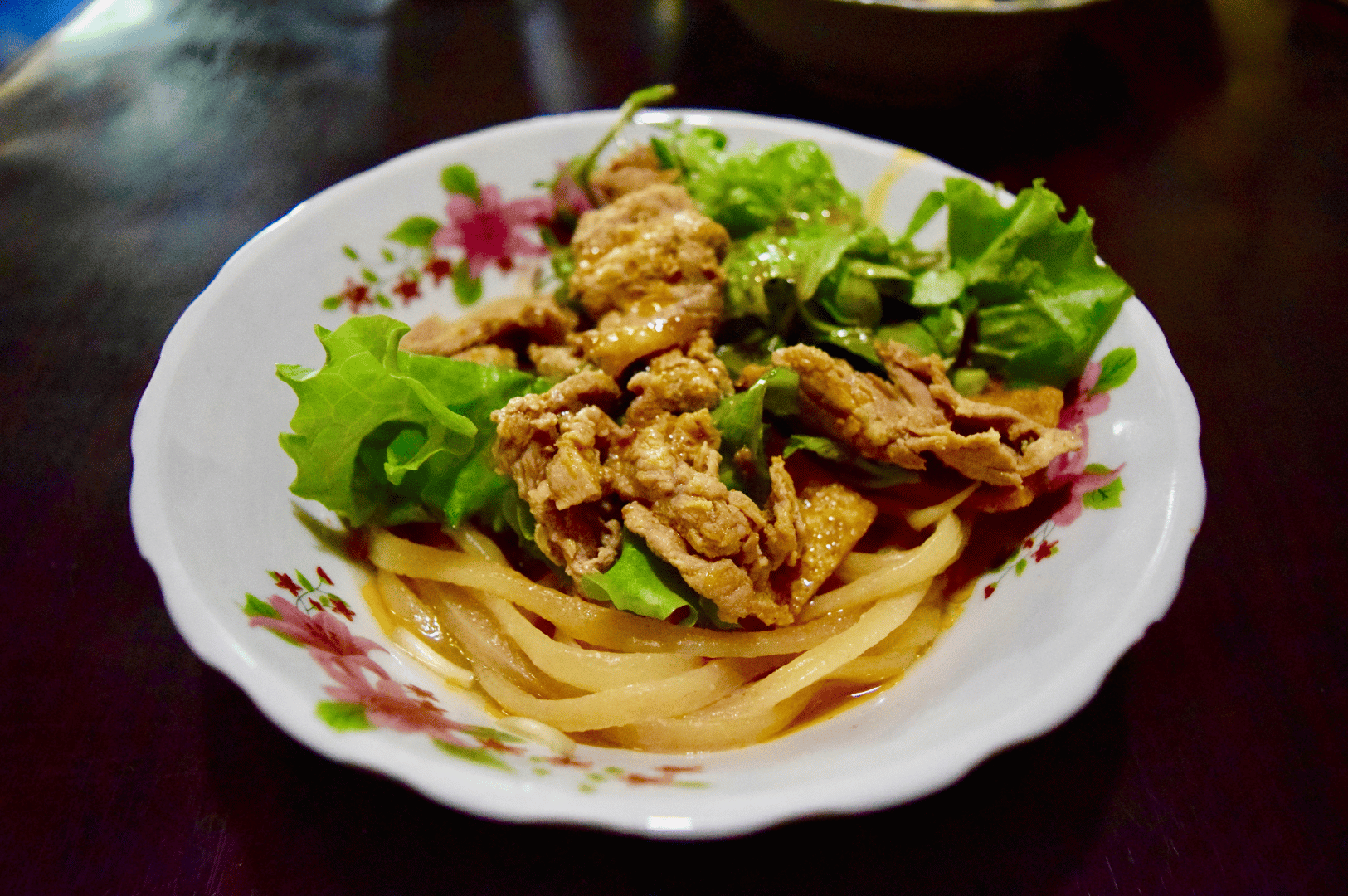

Every serving of authentic Cao Lau begins—and ends—with careful ingredient selection. The chewy, golden brown noodles, known as cao lầu noodles, are made from high-quality rice, soaked in a lye water solution sourced from the Ba Le well. This well, acclaimed throughout Hoi An, produces water with unique mineral content; when mixed with lye from wood ash on Cham Island, it gives the noodles their signature chewy texture, firmness, and subtle smoky notes—making them unlike any other rice noodles in Vietnamese cuisine, or even other ancient town favorites like mi quang.

These noodles are rarely found outside Hoi An, as only local water and traditional lye result in authentic Cao Lau noodles. Once soaked and cooked, the rice is ground, then steamed into sheets, sliced into thick ribbons, and some reserved for deep fry to create crispy rice crackers or croutons. These crackers—sometimes called “pork crackling”—are fried until golden brown, offering the vital crunch in every bowl.

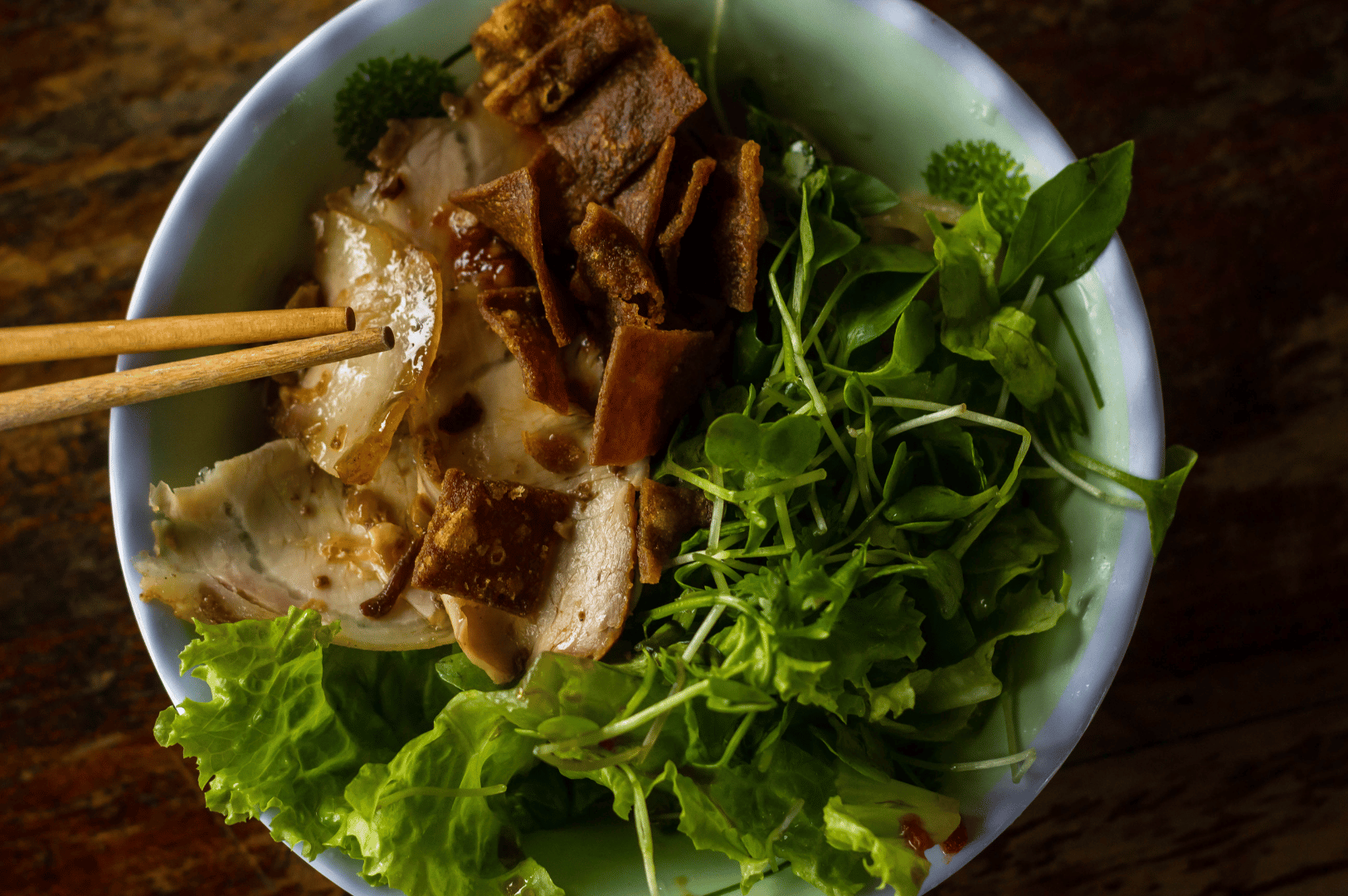

But no Cao Lau is complete without its marinated pork. Traditionally, pork shoulder or belly is prepared with a rich pork marinade: a blend of soy sauce, fish sauce, garlic, sugar, five-spice powder, salt, and black pepper. The marinated pork is then slow-cooked until tender, sliced into thick pork slices, or sometimes grilled pork, echoing the char siu pork of Chinese cuisine. The resulting pork marinade is cooked down with chicken stock and pork bones, producing the dish’s signature minimal broth—more of a sauce to coat the noodles than a soup, intensifying each bite's flavor profile.

Serving wouldn’t be complete without fresh greens and herbs: lettuce, bean sprouts, mint, basil, and often morning glory signature leaves, usually from Tra Que Vegetable Village, a celebrated source for the finest herbs and fresh green vegetables around Hoi An. The addition of crispy rice crackers, fried peanuts, or even white rose dumplings on the side, makes the dish both visually stunning and complex in texture. Every bite brings together pork, herbs, noodles, fried elements, and the nuanced interplay of savory, umami, and herbal notes that define this unique noodle dish.

The Traditional Preparation Process: Ba Le and the Art of the Noodle Dish

Creating a bowl of authentic Cao Lau is an act of devotion. The process starts days in advance with meticulous rice selection—cleaned, soaked in lye water from the Ba Le well, then ground and mixed with boiling water. This creates a thick paste, which is steamed into pliable sheets, then hand-cut into noodles. Some sheets are deep-fried for rice crackers, creating the dish’s signature contrast between chewy noodles and crispy, golden brown elements.

For the pork, Hoi An chefs trust an age-old pork marinade that blends soy sauce, fish sauce, garlic, sugar, salt, pepper, and five-spice. The marinated pork is seared in a hot pan, then slow-cooked or roasted, producing pork slices rich with umami and herbs. The drippings and cooking liquid, combined with chicken stock and pork bones, reduce to a lush, minimal broth—used sparingly to keep each bowl balanced and not soupy.

Assembly brings everything together: a base of fresh greens and bean sprouts, a nest of cao lầu noodles, succulent grilled pork or char siu pork slices, a ladle of the deeply flavored minimal broth, and a crown of crispy rice crackers or pork crackling. Herbs and greens from the vegetable village, fried shallots, and sometimes a touch of green chilli or pepper complete the bowl. "The noodles must be chewy, the pork deeply marinated, the broth concentrated, and every flavor harmonious in one serving," a local chef shares.

Cultural Significance of Cao Lau, Mi Quang, and Hoi An

Within Hoi An, Cao Lau is not merely food; it’s a badge of heritage, culinary storytelling, and local pride. This authentic noodle dish stands as a UNESCO-recognized tradition, reflecting Hoi An’s history of embracing outside influence—whether from Japanese cuisine, Chinese food, or other Southeast Asia traditions. Both locals and travelers view it as a point of pride—a dish to eat at a favorite family-run stall, share among friends, or feature in Hoi An culinary tourism.

Tourists see Cao Lau as a rare treat, eagerly sampled alongside mi quang and white rose dumplings, while locals cherish it as a dish filled with memory and belonging. Through local markets and bustling street food stalls, the presence of Cao Lau, mi quang, and other ancient town specialties illustrates Hoi An’s fusion of the old and new—preserving its identity through food and inviting everyone to taste a story centuries in the making.

Where to Find the Best Cao Lau in Hoi An Ancient Town

The search for the best Cao Lau in Hoi An ancient town is a joyful journey for any lover of Vietnamese cuisine. Authentic bowls are most often found at traditional street stalls or time-honored restaurants, where cooks stay faithful to the culinary roots—using Ba Le well water, lye solution, and fresh herbs from Tra Que.

Top options for an unforgettable noodle dish:

- Cao Lau Ba Be: Central Market food court; local favorite; classic flavors. Extra cost for a loaded bowl is minimal, making it an essential stop for budget travelers.

- Morning Glory Signature: A slightly upscale restaurant celebrating Vietnamese food in the ancient town, known for balance and a consistent serving of fresh greens.

- Quan Cao Lau Thanh: Just outside the tourist center, famous for hand-cut cao lầu noodles, a rich pork marinade, and deeply flavored broth.

- Hoi An Central Market Stalls: Lively, local, and wallet-friendly, with bowls crafted fresh to order—watch for cooks using Tra Que greens for authentic experience.

- Ty Cao Lau (Phan Chu Trinh): Family-run, brimming with fresh herbs, pork slices, and plenty of green chilli for those seeking a little heat.

Expect to pay between 30,000 and 75,000 VND per serving, depending on portion size and location. Arrive early—by lunch or early dinner—as stalls often sell out of their authentic cao lau noodles before nightfall. When choosing, look for a bowl with thick, dark noodles, minimal broth, and a mountain of fresh greens and fried toppings. Ask stallholders about their pork marinade and Ba Le well water for the full story behind every dish.

How to Eat Cao Lầu and Grilled Pork Like a Local

Eating Cao Lau is a feast for the senses, and there’s a local etiquette to enhance the experience. First, thoroughly mix the noodles, fresh greens, bean sprouts, pork, pork crackling, and minimal broth—so each bite is a vibrant, lively blend. Customize with condiments: a splash of fish sauce, a squeeze of lime, a dab of green chilli, and a sprinkle of pepper. Taste, adjust, and enjoy every mouthful.

Chopsticks and a spoon are the tools of choice; don’t be shy about slurping noodles—a sign you’re savoring the flavor. Pair your bowl with iced tea or a local beer (a classic drink in Hoi An). Share food and side dishes, like white rose dumplings or fried spring rolls, and take your time to fully appreciate this ancient town ritual.

Modern Interpretations: Cao Lầu Noodles and the Noodle Dish Unique to Hoi An

Contemporary chefs across Vietnam and abroad are paying homage to Cao Lau with creative takes while honoring tradition. Vegetarian adaptations may swap grilled pork for marinated tofu or jackfruit, maintaining the concentrated pork marinade flavors with a blend of soy sauce, garlic, five-spice, and vegetable broth. Fusion efforts sometimes use udon or thick rice noodles when cao lầu noodles are unavailable—always striving to replicate the chewy texture, crispy rice crackers, and minimal yet bold broth.

While purists insist that the unique noodles and combination of Tra Que herbs and Ba Le well lye solution are essential, modern approaches showcase the dish’s capacity for reinvention and adaptability—true to the spirit of both Hoi An and Vietnamese cuisine. Even when extra cost or local ingredient substitutions are required, the heart of Cao Lau lies in its textures, flavors, and sense of place.

Simplified Recipe for Ba Le Cao Lầu Noodles at Home

Though replicating authentic Cao Lau outside Hoi An is nearly impossible, you can cook a satisfying version at home. Here’s a simplified, globally-accessible take:

- Noodles: Use Japanese udon or thick rice noodles to mimic authentic cao lầu noodles.

- Pork: Create a pork marinade with soy sauce, fish sauce, garlic, sugar, salt, pepper, five-spice, and a splash of chicken stock. Marinate pork belly or shoulder for at least two hours, then sear in a pan and simmer with pork bones and water until meltingly tender. Slice thinly for serving.

- Rice Crackers: Deep fry wonton wrappers or bits of leftover noodles to mimic the golden brown crisp of Hoi An rice crackers.

- Assembly: In a large bowl, add bean sprouts and lettuce, a portion of noodles, pork slices, a few spoonfuls of minimal broth. Top with fresh greens, mint, basil, crispy crackers, and morning glory. Finish with fried shallots, roasted peanuts, green chilli, and a squeeze of lime.

Tip: To achieve the most authentic taste, focus on the noodles' chew, flavor-packed pork, and the interplay of crispy, fresh, and savory. Sourcing fresh herbs or vegetables from a local farmer, or using organic greens, will enhance the flavor. Embrace the spirit of Hoi An’s famous vegetable village and make the dish’s preparation a labor of love—just as generations of cooks before you have done.

Conclusion: Preserving Culinary Heritage — Cao Lau in Hoi An

Cao Lau stands as one of the great noodle dishes in Vietnamese cuisine—a noodle dish unique to Hoi An, shaped by Japanese influence, Chinese foodways, and Vietnam’s resourceful culinary spirit. Every bowl is a tribute to local rice, pork, bean sprouts, fried crackers, Tra Que fresh herbs, and the famed Ba Le well—a harmony that cannot be overlooked by anyone traveling through Central Vietnam.

When you eat Cao Lau in Hoi An’s ancient town, you taste not just a carefully assembled meal but centuries of history, community, and adaptation. Regional specialties like this, rarely found elsewhere, are what make travel memorable and culinary tourism so rewarding. So when you next visit Hoi An, seek out authentic cao lau. Sit among locals, breathe in the savory steam rising from your bowl, and celebrate the enduring story of Hoi An—one unforgettable noodle dish at a time.

To explore more culinary heritage, read about the 5,000-year journey of Chinese tea or discover the rich plant-based traditions of Gujarati thali.

Chicken 65: A Fiery Indian Chicken Recipe You Must Try

Eat Drink Asia Team | February 21, 2026

We’ve spent months tracking the ‘shatter-rate’ of chicken across the South, and here’s the truth: most of what you find is a pale, food-colored imitation. The real Chicken 65 isn’t just spicy; it’s an atmospheric experience. It starts with the sharp, herbal snap of curry leaves hitting 180°C oil and ends with a deep, earthy…

Mastering the Art of Indian Dishes with Chicken

Eda Wong | February 19, 2026

The story of India’s culinary identity is deeply tied to its poultry dishes. I remember my first attempt at an Indian chicken recipe, failing to brown the onions properly left the dish hollow, missing its soul. The sound of mustard seeds popping in hot oil signals layers of flavor to come. The steam from the…

Crunch, Sweet, and Heat: The Irresistible Textures of Southeast Asian Snacks

Dio Asahi | February 17, 2026

In the humid, sticky heat of Southeast Asia, where your shirt clings to your back and the air is thick with the sharp scent of oxidising oil, there’s a particular clink that always gets me. It’s the sound of a metal spatula striking a wok, a rhythmic percussion that’s as familiar to me now as…

The Living Pantry: How Geography and Trade Shaped the Food in the Southeast Region

Eat Drink Asia Team | February 14, 2026

To understand the plate is to understand the map. If you were to trace the spice routes of the 15th century or follow the monsoon winds that carried merchant ships across the Indian Ocean, you would find yourself at the epicenter of the world’s most vibrant pantry. The food in the Southeast region of Asia…

A Symphony of Senses: Why Southeast Asian Food is the World’s Greatest Culinary Journey

Dio Asahi | February 12, 2026

If you were to stand at a busy intersection in Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City, or Jakarta and close your eyes, your nose would tell you a story before your eyes ever could. There is a specific, intoxicating perfume that defines Southeast Asian food: the sharp tang of lime juice hitting a hot wok, the…

The Alchemy of the Wok: The Story of Singapore-Style Bee Hoon

Eda Wong | February 10, 2026

Across the humid evening air of Singapore, a rhythmic clatter echoes from hawker stalls to high-rise kitchens—the sound of a metal spatula against a seasoned wok. Within that intense heat, rice vermicelli noodles undergoes a profound transformation, absorbing the golden hues of curry powder, the savory depths of soy sauce, and the smoky “breath” of…

The Sizzle of the Wok: An Exploration of Fried Bee Hoon Across Southeast Asia

Eat Drink Asia Team | February 7, 2026

Across Southeast Asia, from bustling hawker centers to family kitchens, the sizzle of rice vermicelli noodles hitting a hot wok is a universal comfort. Few dishes capture the spirit of Asian noodle culture as well as fried bee hoon. This stir fry, made with thin rice noodles, delivers a tasty meal any time of the…

The Silk of the East: A Deep Dive into Bee Hoon and the Art of Rice Vermicelli

Eda Wong | February 5, 2026

Across the bustling kitchens of Southeast Asia, one humble ingredient has woven itself into the fabric of countless beloved dishes. Bee hoon, the delicate rice vermicelli that transforms from brittle strands into silky noodles, represents centuries of culinary tradition and innovation. Whether you’ve savored Singapore noodles in a hawker center or encountered fried bee hoon…

The Eternal Hearth: A Journey Through the Soul of Indian Foods Vegetarian Traditions

Dio Asahi | February 3, 2026

In the vibrant tapestry of global gastronomy, few cultures have elevated the plant-based plate to an art form quite like India. While much of the world has recently turned toward meat alternatives for health or environmental reasons, Indian cuisine has been centered on the vegetable for millennia. This isn’t merely a dietary choice; it is…

The Essence of Jeju Citron Tea: A Distinctive Profile of Yuja Tea in Korea

Dio Asahi | January 31, 2026

Imagine sitting in a quiet, sun-drenched teahouse overlooking the dramatic volcanic coastline of Jeju Island. The steam rising from your cup carries an aroma that is at once familiar and yet entirely new—a version of Korean citron tea, or yuja cha, that tastes of sea salt, volcanic soil, and generations of island tradition. As you…